The renowned scientist and doctor shares about his new partnership with Hong Kong biotech company Prenetics, which will see the development of affordable DNA tests that can detect multiple forms of cancer

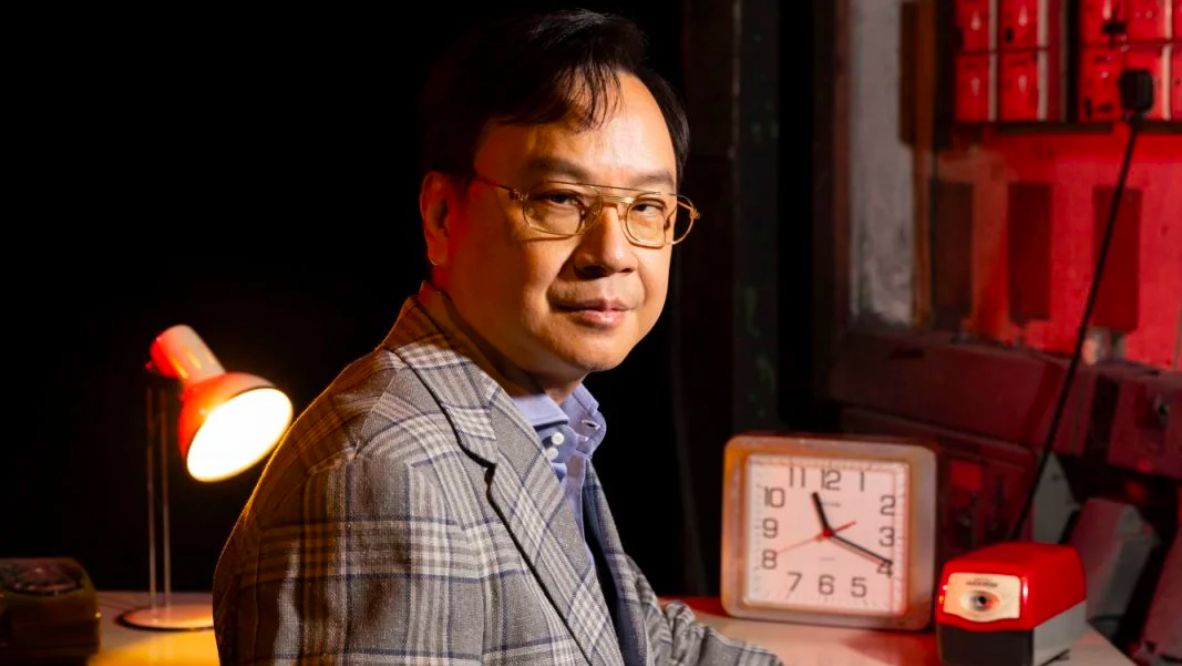

Dennis Lo, Tatler Hong Kong’s July cover star and director of the Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences at the The Chinese University of Hong Kong, is partnering with Danny Yeung, co-founder of Prenetics and an Asia’s Most Influential honouree, to launch Insighta, a company that will offer a new, revolutionary genetic test for cancer, in a deal announced on 26 June.

“Cancer is one of the biggest diseases faced by mankind, and one that has cut short so many lives, including many of my own friends and family. I wanted to do something about that,” Lo tells Tatler.

“[Dr Lo’s] technology is a huge breakthrough,” Yeung tells Tatler. “Our plan is to leverage our existing capabilities in genetic testing, data analysis, and bioinformatics to validate, optimise and scale this technology. It’s about merging our resources with this incredible scientific breakthrough to create a solution that’s scalable and accessible.”

The US$200 million joint venture marks one of the largest private life sciences deals in Hong Kong, and one of the largest in the region, in 2023. Lo and his research team have already developed a test to detect liver and lung cancer using only a sample of a patient’s blood; clinical trials will begin with 5,000 patients early next year. It is expected to be commercially available in Hong Kong and mainland China in 2025. Perhaps most revolutionary of all will be the price of the new test: a mere US$200.

Read our July cover story with Dennis Lo below.